This introduction appeared in Flashing Swords! #1 (Garden City, New York: Nelson Doubleday, 1973). I didn't find a copy of this intro online already and feel that it was well written and contains a lot of great information. If you notice any typos, etc. please let me know and I will fix them as soon as possible. It should be identical to the original.

This book contains four Sword & Sorcery novelettes, averaging 15,000 words each, from some of the most popular writers in this genre. You will find herein a Fafhrd and Gray Mouser yarn by Fritz Leiber, a "Dying Earth" story by Jack Vance, a Viking Age swashbuckler by Poul Anderson, and the first story in a new series - that of Amalric the Mangod of Thoorana - by Lin Carter.

And best yet: you have never read any of these stories before, because they were all written especially for this anthology and have never been published anywhere until here and now.

If you are a Sword & Sorcery buff, the above ninety-nine words should cause you to emit a shrill yelp of joy; at the very least, they should kindle a gloating gleam of anticipation in your eye.

If you are not a Sword & Sorcery buff, well, this book will introduce you to one of the most lively and entertaining schools of fiction popular today, and just might convert you to it.

If you belong to the second category, you might well ask: "What does 'Sword & Sorcery' mean?" A succinct definition follows:

We call a story Sword & Sorcery when it is an action tale, derived from the traditions of the pulp magazine adventure story, set in a land or age or world of the author's invention - a milieu in which magic actually works and the gods are real - and a story, moreover, which pits a stalwart warrior in direct conflict with the forces of supernatural evil.

While the term, Sword & Sorcery, was coined by Fritz Leiber, himself one of the ablest living practitioners of our craft, the genre itself was founded by a young writer named Robert Ervin Howard. Born in 1906, Howard lived in the town of Cross Plains, Texas, for the better part of his short life (he died at thirty), and produced an amazing quantity of pulp fiction and miscellaneous macabre verse which has, thus far, outlived it's creator by thirty-four years.

While Robert E. Howard wrote everything under the sun from pirate sagas to tales of Oriental intrigue, cowboy yarns and ghost stories to sports fiction and murder mysteries, he achieved his highest fame as the creator of Conan of Cimmeria, a wandering barbarian adventurer who roved from one gorgeous walled city to the next across a savage and splendid world of prehistoric magic and magnificence in a shadowy and mythic age which lay between the fall of High Atlantis and the rise of ancient Egypt and Chaldea.

These stories appeared in that most glorious of all the fiction pulps,

Weird Tales. Although in direct competition with brilliantly gifted and enormously popular fantasy or horror writers like H.P. Lovecraft or Clark Ashton Smith, Henry Kuttner or C.L. Moore, Howard's Conan stories were among the most popular ever printed in that pioneer fantasy magazine. They had a vigor, a drive, a surging pace unusual in fiction of that period (the early 1930's), and they were told with superb gusto and verve and enthusiasm by a born master of the art of tale-telling.

So popular did this exciting new blend of the adventure story, the imaginary world fantasy, and the tale of supernatural horror, become, through Howard's fiction, that when he died in 1936 a number of talented writers stepped forward to fill the gap in the pages of

Weird Tales left empty by his demise.

Howard, you see, had done something that no one had ever quite done before...and this, unless it be a self-defeating experiment, like the prose of James Joyce or the poetry of Ezra Pound, which are too inimitable and too completely personal ever to be successfully imitated, much less continued by other hands...this sort of thing, I say, makes other writers eager to try their hand at this new variety of fiction.

Thus, hardly before the sod of Cross Plains, Texas, had covered the burly, two-fisted author who had, in his time, earned more money than anyone else in the town, including the local banker, other writers - like Henry Kuttner, with his Elak of Atlantis stories, and Kuttner's wife, C.L. Moore, with her delightful Jirel of Joiry tales - began contributing to what became in a very short time a whole new genre of pulp fiction.

That was, as I say, thirty-four years ago. Today, more than a third of a century later, there are at least eight writers who have either earned their chief laurels or done their best work in the popular field of Sword & Sorcery.

Examples of the work of four of them you will find in this book; the other four appear in its second companion volume,

Flashing Swords! #2. Here is how these twin anthologies came about.

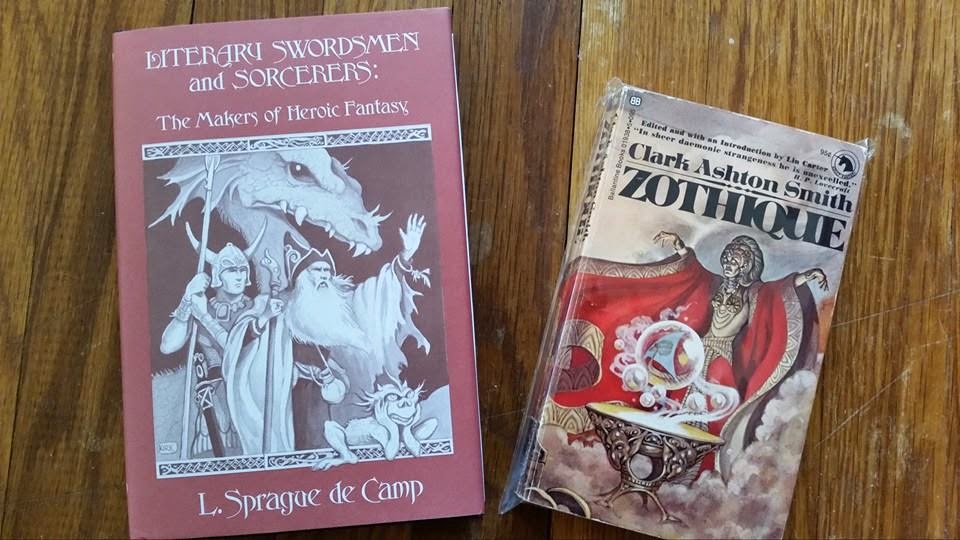

Writers, most of 'em anyway, are fairly gregarious people and enjoy gathering together with their colleagues to talk business, craftsmanship, and mutual problems. Hence the murder mystery writers belong to a guild called Mystery Writers of America, science fiction writers to a guild called Science Fiction Writers of America, and so on. About three years ago, during the course of a three-way exchange of correspondence between myself, L. Sprague de Camp, and John Jakes, somebody (I think it was me) suggested we Sword & Sorcery writers should also form a guild. Whereas these other, older, larger organizations have scores or hundreds of members, hold annual banquets, bestow yearly awards, and all that sort of thing, we authors of S&S - all eight of us! - would form a genuine do-nothing guild whose only excuse for existing would be to get together once in a while and hoist a few goblets of the grape in memory of absent friends.

Think of it - an author's guild with no crusades, blacklists, burning causes, or prestigious annual awards! A far-flung legion of kindred craftsmen, with no fees, dues, tithes, or weregild. It was a revolutionary concept, and The Swordsmen and Sorcerers' Guild of America, Limited - or "S.A.G.A.," for short - was born on the instant, with three founding members.

As I recall it, de Camp was honored with the title of Supreme Sadist of the Reptile Men of Yag, Jakes received the honorific of Ambassador-Without-Portfolio to the Partly Squamous, Partly Rugous Vegetable Things of the South Polar City of Nugyubb-Glaa, while I basked in the pleasures of the aristocratic title of Purple Druid of the Glibbering Horde of the Slime Pits of Zugthakya.

You may be familiar with the work of one or another of us in certain other fields, such as science fiction or historical novels or whatever; but John Jakes has for years authored the Brak the Barbarian stories, and Sprague has written a number of heroic fantasies laid in his version of Atlantis (a place called Pusad), while I have thus far produced something like half a million words of swashbuckling fantasy about the adventures of Thongor the Mighty, barbarian warrior king of the Lost Continent of Lemuria.

Anyway, intoxicated with our organizational triumphs, and heady with our success in coining pompous and ridiculous titles for each other, we stopped to consider who else deserved membership in what would always be one of the smallest and most exclusive of all writers' guilds. Fritz Leiber, creator of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, of course, came to mind first; and Jack Vance, for his gorgeous "Dying Earth" yarns; and Michael Moorcock, a young English writer who had won an enthusiastic American audience with his spectacular Elric stories. These worthy gents were, in good time, informed of their unanimous election to our ranks.

Somewhat later the membership, then six, was polled and agreed that Poul Anderson belonged with us on the strength of two splendid novels,

The Broken Sword and

Three Hearts and Three Lions. And Andre Norton, too, our only Swordswoman & Sorceress, for her fine "Witch World" series.

So now we are eight.

It was at the World Science Fiction Convention in St. Louis in 1969 that John Jakes or Fritz Leiber or somebody suggested that, with all this raw talent in our ranks, we should pool our octuple abilities and produce an anthology of Sword & Sorcery stories of such stunning brilliance as to rock the work-a-day science fiction world back on its collective haunches. As an added fillip - to say nothing of a key inducement to an amenable publisher - it was decided that the anthology should consist of

all-new Sword & Sorcery stories, just as Damon Knight's annual

Orbit consists of all-new science fiction yarns.

A charming editrix, Gail Morrison of Dell Books, liked the idea and requested an original 15,000 worder from each of us, that being, in the opinion of many writers, just about the best length for a good story. The Supreme Sadist of the Reptile Men of Yag gently pointed out that this would make a book of 120,000 words - a tome of somewhat ponderous dimensions. Mrs. Morrison just smiled and said that in that case she would make

two paperbacks out of it, thus doubling Dell's potential profits; and, in the same breath, she named an emolument so princely that we promptly addressed ourselves to our respective IBM Electrics.

The first volume of the result you hold in your hands.

The fine old art of Sword & Sorcery writing has evolved quite a ways from the era of Robert E. Howard, Conan the Cimmerian, and

Weird Tales.

Some writers, myself among them, have been content to employ as a setting for our yarns, the mythic epock which preceded history, as Howard originally did when he set his Conan saga in an imaginary "Hyborian Age" of his own invention.

Others, like my esteemed colleague, Jack Vance, have gone exactly the other direction, and chose the very distant future for their scenery, an earth grown old and gone back again to the primal magic and wizardry it knew in its youth.

Yet others, like Fritz Leiber and John Jakes and Andre Norton, have taken completely imaginary other-worlds as the milieu for their fine stories.

You will find a little of everything, then, in this book and in its companion volume.

You will also find all sorts of stories. Stories with verve and sparkle, wit and polish; stories frankly humorous and stories of sheer, headlong adventure and excitement; stories of action and stories of subtler mood.

But all share one thing in common; they are all tales of swordsmen and sorcerers, in worlds or lands or ages where magic works...

LIN CARTER

Hollis, Long Island, New York